Meditation and the Art of Chinese Peony Painting

The experience of practicing Transcendental Meditation and creating a Chinese peony flower painting have a lot in common. The term that comes to mind is ‘effortlessness.’ The practice of TM supports the creative art of Chinese ink and watercolor brush painting; it helps prepare the mind and physiology of the artist to engage in the specific creative techniques. A peony flower picture with a rock and a few blades of grass will help us understand.

The stability and alertness gained from the TM technique are qualities required for Chinese painting. The single, strong brush stroke is the central feature of a traditional Chinese painting. Whether creating a dot-like stroke by the gentle laying on of pressure from the tip to the middle of the brush without actually moving the brush, or by pulling the brush along to create a linear stroke, one needs concentration to achieve steady continuity in motion. Strokes that are accomplished in this way have a kind of springiness and spontaneity. They are natural and strong, and do not look labored or worked at. These strokes are the expression of the qualities of both silent tenderness and strength—the inner, hidden realm of ‘being’ is expressed in an outward motion or flash.

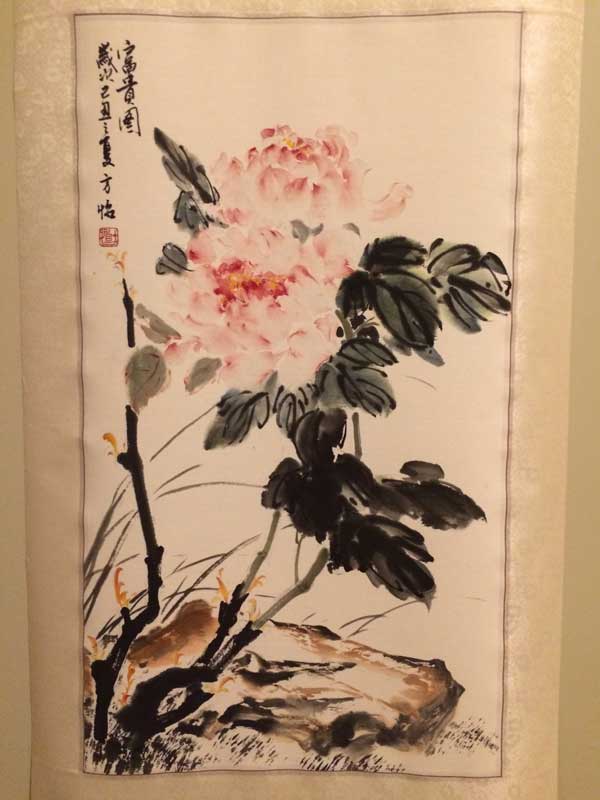

There are two levels of appreciating and ‘reading’ a Chinese painting. First, there is the level of seeing how the flower, bird, person, or rocky mountain and waterfall are depicted realistically. For example, Is the flower skillfully drawn, and lovely to look at? The painting here shows how the delicate strokes in the flower, with deeper red at the tips, allow for the creation of volume, making the peonies look full and round, with almost a vessel shape. There is also the symbolic meaning: peony flowers are thought to enhance prosperity, wealth and the social standing of the family. Moreover, since the role of the woman in traditional China was in the home, the meaning of the peony also suggests the qualities of the mother and the wife. Many homes as well as family businesses still have a peony painting in a prime location.

The second level of appreciation is more abstract and relates to the separate strokes mentioned above. The gentle touch and laying on of the strokes is sometimes rapid and spontaneous, while other times it is accomplished through more deliberate and careful work. Both types of strokes emerge from the same source, the conscious state of the artist and the unity of hand and mind. The impetus of where to lay the next stroke, the speed and timing of laying them down, one following the other in rapid succession, or emerging slowly and deliberately—both ways of brush work create variation and lead to a kind of musical rhythm forming a harmonious whole on the page. There are also water and color variations in each stroke. The brush can be loaded with two or three colors, which are actually mixed on the brush with the water as the stroke is laid down creating single strokes with two or three colors. Sometimes the brush strokes are dry and have less pigment or ink, and there are white streaks showing; this is called ‘flying white.’ The observer who understands these many qualities will enjoy following the direction, strength and rhythm of the strokes above and beyond the realistic depiction in the painting. Therefore, the benefits gained from TM are important, not only when doing paintings, but also when looking at them. One is free to jump in and visually and viscerally ride and dance the strokes and also to feel how they connect via the natural energy impetus moving from one to another to another to create the whole painting, which is almost like a map with pathways and hiking trails. Therefore, for this second level, the strokes as they unfold are a concrete visual record of the mental process, the transcendent consciousness of the artist as expressed in the painting.

Often an artist will Imaginatively visualize the painting composition before beginning to paint. She might even make a light sketch with water on the blank paper. This image nestled in her mind will guide her in laying down the strokes. I have found that Transcendental Meditation helps imprint the composition in my memoryduring painting and keeps me on course during the process. It also helps me to know when to let the imaginative composition go and develop the painting in another direction.

Maharishi, the founder of the TM program, had great interest in and often spoke of the Dao (Tao), and the philosophy of Daoism (Taoism) in Chinese culture. The ancient Chinese literature also speaks of something called the ‘Dao of Painting,’ an experience which is achieved after much practice. Like meditation, mastery of the Dao of Painting cannot be forced; painting in this way is not a struggle. After several months of steady practice of Chinese calligraphy for 3 or 4 hours a day, I was lucky enough to have an experience where the brush in my hand seemed to move on its own and the painting to have been created by nature itself. I sat there in awe, watching it happen. Indeed, this is what Maharishi calls “Spontaneous Action.”

According to the Chinese vision of yin and yang, the yin (feminine principle) is an inner quiet space that corresponds beautifully with the cultivation of the silent, inner quality of stability in Transcendental Meditation. This feminine principle is the source of the quiet effortless energy underlying all creativity, from the rocks, mountains and waterfalls, to the artistic expressions of humans.

Maharishi was often surrounded by flowers when lecturing and teaching. We are the flower, as we are one with all in the world. And the act of painting is a communion of the artist and the flower. She pours the love and energy from the deepest level of conscious being into the visual image. The gentle touch of the brush, effortless creativity, reaching out to the on-going, eternal self.

The stability that comes from TM provides a firm base, a grounding, a spring board that sets the hand free to take off. Like the gentle but firm mother who is the stable support for the child as she experiments and creates herself, the steadfast inner stability supports the hand moving the brush from stroke to stroke as it takes off and flies, here to lay out the delicate flower petals, there to define the cascading leaves and strong and firm stems, to establish a broad orange and brown rock platform, the effortless dynamism of nature, the process of improvisation in the spiraling strokes. This is the ‘Dao of Painting’, the source of creativity. TM helps both in creating and appreciating the subtle and dynamic qualities of a Chinese painting.

About the Author

Demerie Faitler is a PhD in Chinese History. She has spent several years studying the art of Chinese brush painting with leading experts in the genre in Taiwan, where she lives and paints for part of each year.